Though we often don’t think about them in this way, dogs are really about people — those long-ago (or, sometimes, not so long-ago) figures who developed particular breeds for particular tasks. Some breeds — like the Doberman Pinscher, Teddy Roosevelt Terrier, and Cesky Terrier — owe their existence to just one visionary person. Other breeds were brought into being by specific cultures or classes of people.

If civilization is the intersection of a group of people with their environment, so too are their dogs: With coats that evolved to survive the local climate, body styles developed to navigate native terrains, and characters that fit into the social mores of the day, our purebred dogs are living, breathing moments of history, reflections of the far-flung cultures that developed and nurtured them. Through them, we rediscover our globe’s cultural diversity and heritage.

Each week, without even leaving our couches, we travel to a different place and time to meet the people who developed the snoozing bundles of fur at our sides.

***

Doggie day care usually doesn’t result in a new breed. Then again, most pooches aren’t babysat by 19th-Century big-game hunters.

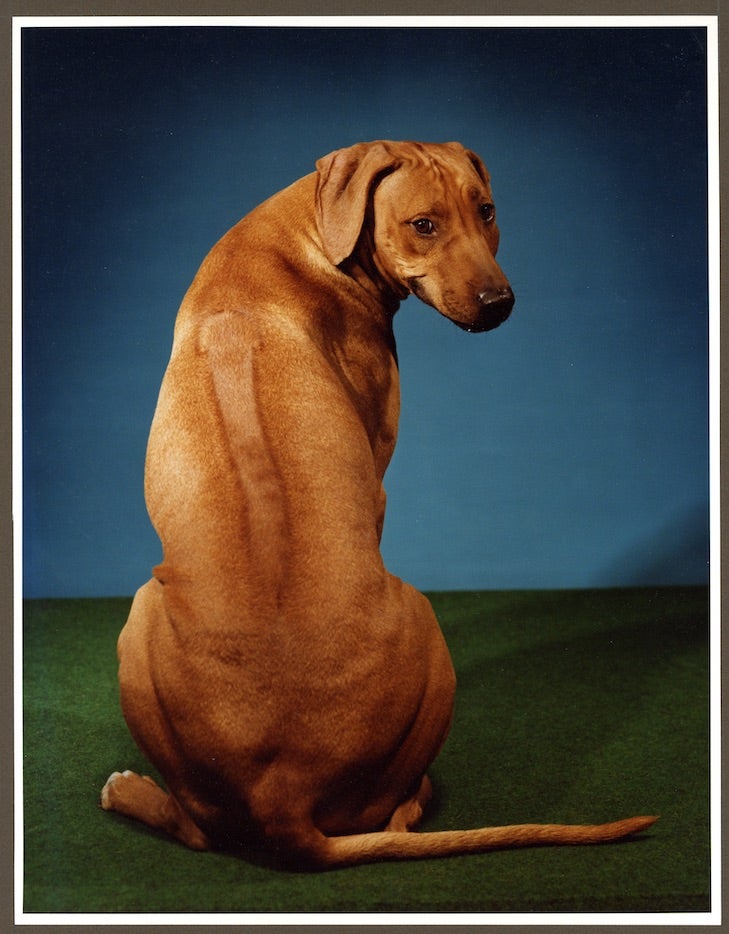

As its name plainly indicates, the Rhodesian Ridgeback is a dog with a ridge on its back that originates in Rhodesia. (Though that country in southern Africa is now known as Zimbabwe, the breed’s original name abides. No Zimbabwean Zipperbacks here.)

Before we get to the dog-sitting episode that brought these famed lion-hunting dogs into being, we have to turn back the clock and head south, to the tip of the continent.

There, in the mid-1600s, the Dutch East India Company established a port at the Cape of Good Hope where ships could refuel and restock on their way to and from the tea markets in Asia. The Dutch settlers noted that the native peoples, called the Khoikhoi, had dogs with unique, backward-growing stripes of hair up their backs. Though not particularly attractive with their pricked ears and jackal-like bearing, these ridged dogs were hardy and had a seemingly innate ability to survive encounters with African predators, in particular lions.

Eventually, the Continental breeds brought to South Africa by these colonists, who called themselves Boers – Dutch for “farmer” – crossbred with the native dogs. There were no organized breeding programs, but, being a dominant trait, the ridge persisted, in the Boer dogs as well as the Khoikhoi ones.

A Pack of Lion-Hunting Dogs

Some 200 years later, in 1875, the Reverend Charles Helm left the Cape and traveled north in an ox-pulled wagon to Hope Fountain, in the southwest corner of then-Rhodesia, to run the mission there. He was accompanied by his wife, their infant daughter, and Powder and Lorna, two presumably ridged female dogs said to resemble rough-coated Greyhounds.

One of the few outposts on the way to the bustling settlement at Bulawayo, Hope Fountain Mission was an essential stopping place for travelers, weary hunters and fellow missionaries. The famous hunter and explorer Frederick Courtney Selous convalesced there after walking – and partially crawling – 400 miles from the Zambesi River in a feverish delirium.

Another professional hunter and close friend of Selous also knew the Mission well. Cornelius van Rooyen – “Nellis” to his friends – was married there four years after the Helms family arrived. A Boer living in British-centric Rhodesia, van Rooyen was a famed big-game hunter, arranging expeditions for the wealthy and influential, including English dukes and lords. Returning from his expeditions with horns and hides, he also captured wild animals and sold them to European zoos and wildlife parks.

For these dangerous endeavors, he required a pack of lion-hunting dogs, whose ranks were constantly winnowed by the teeth and claws of their prey.

The biggest misconception about Ridgebacks and lions: The former never made contact with the latter, but rather teased and disoriented them, much as a matador taunts a bull.

When business required him to travel back to South Africa, the Reverend Helms would leave his dogs with van Rooyen. Because spay and neuter was hardly a priority in the African bush, the females interbred with von Rooyen’s pack, which was believed to include Greyhounds, Irish and Airedale terriers, Collies and Bulldogs, which were longer-legged and more agile than the breed we know today.

Backs With Ridges

It’s not known if van Rooyen selected Lorna and Powder’s puppies based on whether there they had a ridge or not. (Even today, a certain percentage of Ridgeback puppies are born ridgeless.) Instead, nature was likely the ultimate arbiter, because in the end only the strongest and smartest survived. But as time progressed it became clear that the ridged dogs were more successful hunters, likely owing to their native Khoi dog blood.

Lion-hunting required a specific set of both physical and mental skills: The dogs had to be strong enough to withstand the physical rigors of the hunt, but have ample agility to dart out of the way of slashing claws. (That is the biggest misconception about Ridgebacks and lions: The former never made contact with the latter, but rather teased and disoriented them, much as a matador taunts a bull.) The dogs had to be courageous enough to harry the king of beasts while the hunter positioned himself for the killing shot, but intelligent enough to know if their battle was a losing one, and so know when to retreat.

Not surprisingly, van Rooyen’s Lion Dogs, as they became known, developed quite a reputation, becoming so noteworthy that Selous mentioned them in his famous 1893 book, “Travel and Adventure in South East Africa,” including a dog that resembled a “mongrel deerhound” that van Rooyen “would not have parted with at any price.”

That particular dog died during the hunting trip Selous was recounting. Van Rooyen too died before his time, at age 55 of pneumonia. While never intending to create a breed, van Rooyen nonetheless did, taking a hallmark trait that was commonly found among the first dogs his Boer ancestors had encountered, and making it indelibly associated with the kind of fortitude and savvy needed to survive in their beautiful but dangerous new homeland.

Speed and Endurance

As final recipes go, however, the Ridgeback was only half-baked. Fanciers in the early 20th Century began to breed the dogs more as the all-around companions and protectors that they had always been rather than for the dying sport of lion hunting.

The Ridgeback was able to perform a variety of tasks – coursing and bringing down large antelope, fending off baboons, herding the occasional ox, and protecting the kraal, or livestock pen, at night.

They understood that rather than being a one-trick pony, the Ridgeback was the consummate generalist, able to perform a variety of tasks – coursing and bringing down large antelope, fending off baboons, herding the occasional ox, and protecting the kraal, or livestock pen, at night.

Reflecting these diverse roles, in many cases the only thing these early Ridgebacks had in common was the ridge on their backs. In 1922, a meeting of Lion Dog owners in Bulawayo turned out a dizzying assortment of dogs that ranged in appearance and size from Bull Terriers to Great Danes.

Borrowing liberally from the Dalmatian standard, which described a dog that, like their own, needed to be able to trot alongside a horse or wagon all day, these early fanciers crafted the Ridgeback version. They added the details of the all-important ridge, as well as words to indicate this unique African breed needed speed as much as endurance. Since no one dog that was present fulfilled all the criteria of their emerging standard, these dog men took a buffet-like approach, selecting the ears of one, the tail of another, and on and on.

In short order, these early fanciers also changed the name of the breed from African Lion Dog to Rhodesian Ridgeback, because while any dog can, in theory, hunt a lion, not every dog has that telltale cowlick up its back that attests to its roots in the rocky headlands of the Cape of Good Hope. This is why knowledgeable fanciers always refer to their dogs as “Ridgebacks” for short – not “Rhodesians.”

Today’s Rhodesian Ridgeback

If Cornelius van Rooyen were to see his dogs today, chances are he would not recognize them apart from those telltale ridges. With their short, wheaten coats ranging from pale flaxen to rich red, handsome heads and marble-sculptured physiques, modern Ridgebacks are indisputably more polished than their frontier-bred progenitors.

But he would undoubtedly recognize the old souls beneath. Along with the hallmark ridge, the fearless hunter, independent-minded strategist, and canny survivalist remains. And traces of that genetically imparted wisdom are in evidence even today: No matter where they live, Ridgebacks will almost universally refuse to leap into a standing body of water, because such an impetuous act in their native Africa would likely result in being lunch for a crocodile.

Such quirks aside, the most valuable quality that persists in the dog under the ridge is the very same one that caused a seasoned hunter like van Rooyen to mourn each time he returned from a hunt without one of his Lion Dogs. And that is, that a dog of such courage, intelligence and self-possession would choose to love its humans as deeply as it does – a reality that is just as breathtaking as any exotic species you might see roaring across the African veldt.